“Why do you love Italy so much?” my mom asked me at Cafe Florentine in New Hartford, NY over espresso.

“Because it feels like home,” I said.

I grew up in a small town in Upstate New York, mainly consisting of Italian-Americans and Polish-Americans. To no coincidence, my mother’s side mainly comes from Eastern Europe, while my father’s side comes from Italy. Family gatherings always included red sauce and cannolis, and there was never a shortage of my grandpa’s homemade red wine, which I refer to as Rosati red. It wasn’t anything unusual; it was just the way our family typically gathered and celebrated, and still does to this day.

With my grandpa as he cooks, Photo by Kaitlyn Rosati

I can’t say I ever felt like the small town I grew up in was home. I got out of there as fast as I possibly could. I graduated high school early and moved to Los Angeles only two weeks after turning 17 years old. But at some point, I realized Los Angeles wasn’t really home either, so at age 19, I headed over to New York City, where I still currently reside. I was convinced it was the closest thing to home I would ever find.

That all changed in July 2017, when I took a flight from Split, Croatia (SPU) to Venice Marco Polo Airport, Italy (VCE). As I boarded the plane, I felt equally exhilarated as I did humbled to finally visit where my ancestors had come from. I skipped through the streets of Venezia, took a gondola ride by myself with a mini bottle of champagne, ate pasta for more meals than I would have allowed myself to had I been anywhere else, and for the first time in my life I felt… free.

Venice, Photo by Kaitlyn Rosati

Photo by Kaitlyn Rosati

I spent 8 days in Italy on that trip, and when I was at the airport in Rome (FCO), I didn’t feel ready to leave. I had some lingering questions: what part of this beautiful country did my family come from? Do I still have relatives here? I knew I would need to come back to feed my curiosity.

Years later, I left for a round-the-world backpacking trip, and at some point, when I was in India and things had gone awry (that’s for another story), I knew I needed to head somewhere where I was comfortable. I found a ten-hour flight to Milan and booked it to leave that night. I arrived, and that freeing feeling I had felt two years prior in Venice came right back. I skipped around the Cathedral in the rain, and went to Mercato Centrale Milano where I ordered a glass of Rosati wine (not my grandpa’s homemade unfortunately, but actually the Italian name for rosé), a requirement when it’s your own last name.

Rosati wine in Milan

This time, I was in Italy with no plan, and decided to just wing it. I went to Bologna, Florence, Parma, Lago di Como, and more. Locals spoke in Italian to me thinking I was fluent, often saying, “Sorry, you look Italian!” I didn’t care that I was on an epic backpacking trip with the freedom to go anywhere in the world, all I cared about was being in Italy. I had the thought, What if I just never leave? I started exploring how I could possibly move there, what the requirements were to bring my then 7-year old Boston Terrier from New York to Italy, what I could possibly do for work. I visited a school in Florence; could I enroll here? While exploring this idea, I had met a man from Brazil who was there in the final stages of obtaining his Italian citizenship. “How are you doing it?” I asked him. He told me his grandfather was born in Italy, and that he had been able to prove it via birth certificates, along with his immigration papers to Brazil, and that Italy offers a program called jure sanguinis, or “right of blood,” a rule that a child’s citizenship is determined by its parents’ citizenship. I had heard of this prospect before but had heard it was expensive and time-consuming, so I always put it off as something I would do later, or maybe never. But meeting someone who was so close to achieving it changed my perception: it suddenly seemed possible.

I added “get Italian citizenship” to my never-ending list of radical things I hope to achieve in my life, but it wasn’t necessarily a priority at the time. I eventually left Italy for east Africa, ran out of money, returned from my backpacking trip, and only a few short months later after being back in New York, the entire world shut down due to Covid-19.

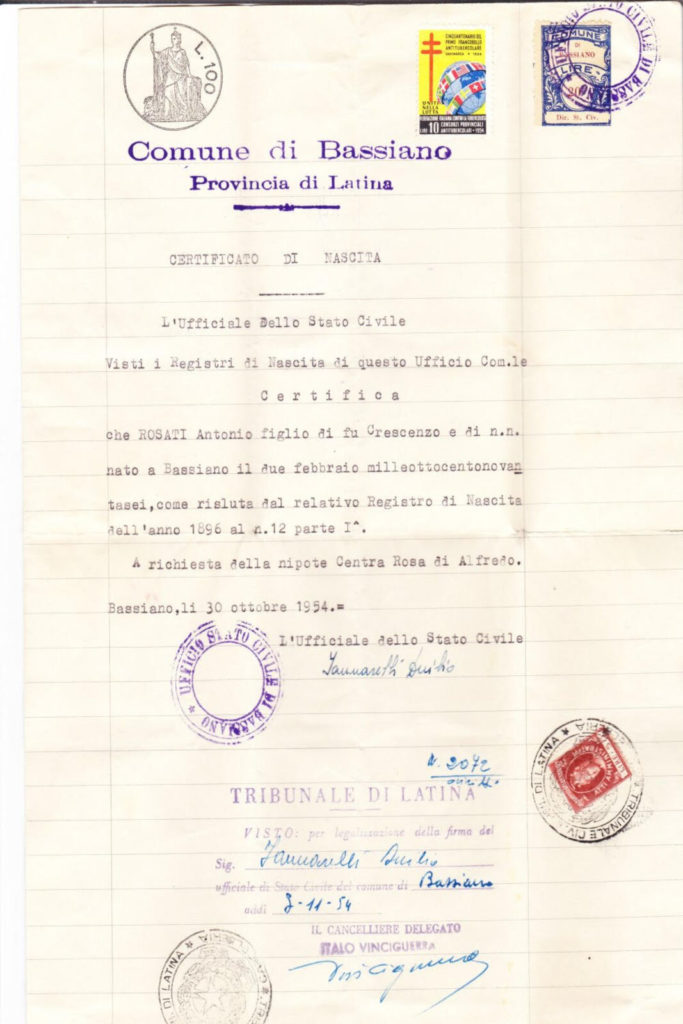

I was pretty bored, and to be frank, severely depressed during Covid-19. I started looking at my radical to-do list. “Book a trip to Antarctica,” “Gorilla trek in Rwanda,” “Get Italian citizenship.” The citizenship option seemed like the only one possible from home, so I signed up for an account on ancestry.com. From there, I was able to get some family members’ names, and learn a little bit about my relatives. My dad had recommended I reach out to a cousin of his who knew a lot about their family’s history. I called her, and she emailed me my Great-Grandfather Antonio Rosati’s birth certificate from 1896, along with his immigration papers, and my Great-Grandmother Giovonna Curto’s immigration papers. I saw that my Great-Grandfather had traveled from Naples to Canada, where he crossed into the USA border, and my Great-Grandmother had traveled from Naples to the USA, arriving on February 14th, 1921. This certainly felt like a good step in the right direction, but I was unsure as to where to go from there. I joined a Facebook group called “Dual US-Italian Citizenship,” where every single day, hundreds of people posted selfies with their new burgundy Italian passports with captions saying, “5 years later and I did it! I’m an Italian citizen!” There were several guides in the group, explaining different routes to take. I learned that jure sanguinis could only be obtained through male lineage, meaning if you were only Italian through your mother’s side, you were out of luck. I didn’t think this would be an issue for me because my great-grandfather was Italian, which was passed onto my grandfather, which was passed onto my father, which was passed onto me, meaning I had a direct line of Italian men in my family. However, the twist is, if the male relative in which you are trying to obtain citizenship through had naturalized as an American citizen prior to giving birth to the next of kin, his citizenship was broken and therefore was not passed down, making you ineligible. Confused yet?

To confirm my eligibility, I had to find my great-grandfather’s naturalization papers. After some digging and searching, I discovered he had naturalized in 1926. This posed an issue because my grandfather was born in 1934, meaning the lineage was broken due to this intricate rule. This meant I could not use the male side to become a citizen. I wasn’t willing to accept the end of my journey because of this one bump in the road. There had to be another way.

My great-grandpa’s immigration papers; Photo courtesy of ROSATI FAMILY

I then learned about the “1948 rule,” where if you are trying to obtain citizenship through a female family member who was born prior to 1948, you can argue a case in court in Rome on the basis of gender discrimination if the lineage has NOT been broken on the female side. Certainly a more expensive and risky route, but still possible nonetheless, I realized this was my only option due to the broken lineage on the male side of my family. I was able to obtain my great-grandmother’s death certificate from Utica, NY, where she died in 1992, but was having some difficulty finding her birth certificate. My dad’s cousin was close with their grandparents, and had told me that my great-grandmother was born in either November of 1902 or 1903 in a small town called Pignola in the Province de Potenza. I googled the town hoping I could make a phone call somehow, but realized it was a small town somewhat in the middle of nowhere in Southern Italy. There are some websites to find public records, and I searched her name in an attempt to find some proof of her existence in Italy online and came up with nothing. I reached out to Francesco Curione, a fabulous resource for anyone trying to obtain citizenship with his company 007 Italian Records, and he said he also saw no record of her. I realized the only way to get to the bottom of this mystery was to fly to Italy myself and ask people in her town. There was one big issue though: Italy had some of the worst cases of Covid-19 and had zero plan to re-open anytime soon.

I didn’t want to lose hope and wanted to keep the momentum alive, so I decided to make good use of my time. I reached out to USCIS to discover when she was naturalized, since this would also play a part in my eligibility. It took a whopping 7 months, but they finally emailed me back and confirmed she naturalized in 1936, which meant when she gave birth to my grandfather Anthony Rosati in 1934, the Italian lineage was passed down to him. This confirmed my eligibility.

Now, the most crucial document in ensuring my eligibility was my great-grandmother’s birth certificate. I was scrolling on my phone mid-May 2021 when the words I’ve been waiting to hear finally popped up in an ad, “Italy is finally reopening to tourism on May 15th on Covid-tested flights.” Despite intense entry protocols, I booked a ticket to Rome, and from there, I would head to the south where I’d finally get to visit my great-grandmother’s hometown and hopefully find her birth certificate.

Two weeks later, I arrived in Southern Italy after a stressful flight and long bus ride there. I was based in Matera, about an hour from Pignola, and hired a driver, Luigi, for the day to take me to the municipio in Pignola. He was speeding because the municipio was closing early that day, and we ended up getting pulled over by the polizia. Getting stopped by police in a different country was an experience; to put it plainly, there was much less fear-mongering. “Sono Americano, mi dispiace, mia bisnonna è di Pignola e sto cercando un certificato di nascita a Pignola,” I muttered nervously. Luigi explained that he was speeding to help me. I showed them my passport, and the police were so friendly that they ended up calling the municipio to tell them to wait for us, and told us to not speed anymore. When we arrived, there might as well have been a red carpet rolled out. The entire staff was out front waiting for me, with warm welcoming smiles on their faces.

Pignola, Photo by Kaitlyn Rosati

Pignola was nothing like any other city I had seen in Italy. This region is particularly poor and prone to more earthquakes than the rest of the country. I was hoping I could buy a postcard or a cute souvenir from somewhere in the town, but there wasn’t even a place to buy a cup of coffee. It was humbling, to say the least. I walked into the municipio, where my temperature was checked due to Covid-19 concerns, and started reciting my extremely rehearsed speech about how I had traveled from New York to get my great-grandmother’s birth certificate. They whipped out a giant pink book that said “1902,” moved to November, and started looking through names. Nothing. They whipped out another pink book, “1903,” and I watched them scan, scan, scan to no avail. They didn’t have any record of her. They searched through a few other years when we all realized it wasn’t there. They recommended I try the church (“chiesa”), so Luigi and I drove, but it was closed. My disappointment was apparent, but I was grateful for the experience. If you ever want to feel tiny in this giant great world of ours, might I recommend a visit to where your ancestors came from? To this day, I still cannot find the words of how I felt there, with or without the vital document I needed.

Luigi drove me to the train station in Potenza, where I’d head on the long journey to Rome. As soon as I sat down, tears began to stream out of my eyes. Now what? It felt like I was so close to becoming a citizen, and yet, arguably the most crucial document I needed didn’t seem to exist.

I have not given up yet. I still have yet to find my great grandmother’s birth certificate, but I plan to go back to Pignola to find a baptismal record, which can be accepted as proof of her being born there. Once I find some type of proof, the next step is to hire a lawyer to fight my case in Rome. I have since discovered I have living relatives all over Italy. I have a distant cousin who is a professor in Turin. I have cousins who live near Pignola in a town called Sasso di Castalda, whom I’ve been in touch with. I have been practicing speaking Italian, often to myself in my one-bedroom apartment in Queens. It somehow all feels painful to feel so connected to my great-grandmother despite never knowing her. What was she like? What was her favorite thing to cook? Why did she come to the USA at such a young age without her parents? What has been even more difficult is in early 2021, we lost my grandfather, her son, to Covid-19. I wish I could tell him about his mother’s village and how they joked that I must be from there due to how short I am, since everyone I met there was also vertically challenged.

Bologna, Photo by Kaitlyn Rosati

It has certainly been a tricky process, but with patience and a pinch of relentless hope, I do believe I will eventually become an Italian citizen. And if this whole thing sounds like a huge pain, and you’re thinking why does this girl need to become an Italian citizen so badly? Well, because to me, I never quite belonged in Utica, Los Angeles, and I sometimes feel like an outsider in New York… but Italy? Italy just feels like home.

Pingback:Itinerary For One Day in Rome, Italy - No Man Nomad

Sono molto dispiaciuto della brutta impressione che ha avuto di Pignola, anche perchè non è così come le è parsa. Comunque, se mi da qualche notizia della sua famiglia provo a vedere se ho qualche traccia da suggerirle

I wanted to thank you for this great read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post…

thank you!